Bombo | A Day at the Clinic

There's a million people whose heartbeats made Uganda what it was, but until the time suitable for a note of dedication...

for Gitta

Monday was the first full day of the clinic. The sun was bright and the sky blue without a trace of rain clouds in the sky. We drove to the clinic in a van that swayed like a reed in the wind at every turn. The final left at the roundabout shot us onto a straight away headed for the clinic where to our right appeared a thick line of people. It took a moment for us to deduce the hundred yard stretch of blurring shapes and colors was Ugandans lining up for our clinic. Bombo Pentecostal Church was already a busy campus of many volunteers in red t-shirts reading, “For God’s Glory.” We turned down the rocky driveway as guards lifted a thin rope serving as a gate. We quickly made our way to various locations to prepare.

In the first moments of Monday morning a little boy caught my eye and gave me the biggest smile. He was being ushered in, but started moving towards me and I to him. His name was Gitta and looked as though he put extra effort into looking presentable for the occasion, his t-shirt carefully tucked into his jeans. He was with a woman and five other children whose relation to one another I am unsure of, except the baby on the woman’s back was her’s. I saw the concept of “it takes a village” to raise a child embraced in Uganda.

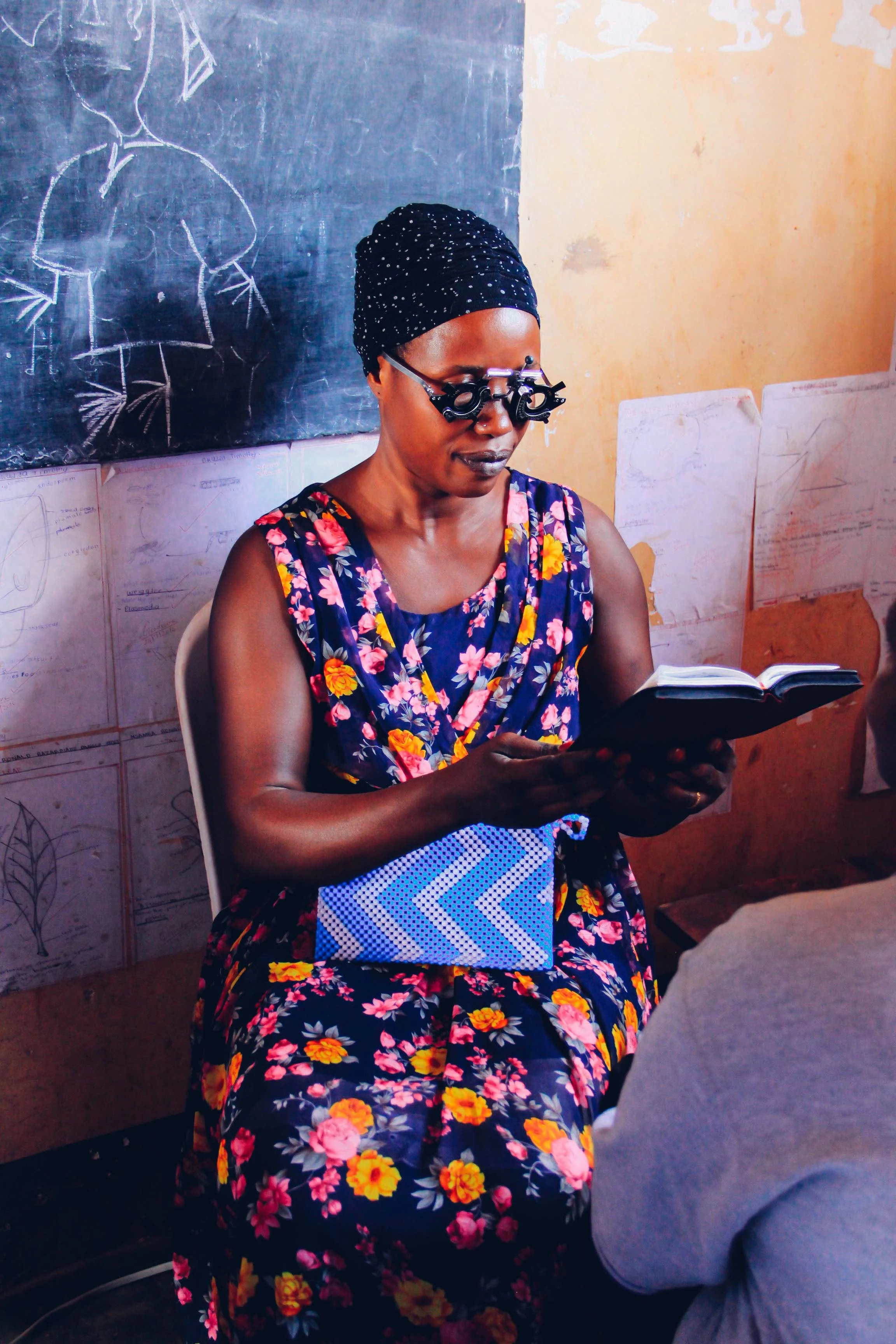

I made my way to Gitta and reached out my hand to shake his, as the adults and children frequently did to greet. Instead, he grasped my hand and held on. I had found my story for the day. I walked with the group of six children and one adult to triage where I asked with a translator if I could accompany them through the clinic. Jeniffer, the guardian, said yes. She was beautiful, tall and in a long, flowing purple floral dress. Her skin was so smooth, dark like a rich caramel, her head covered by a sparkly black cap, and her nose adorned with a golden stud.

Upon arriving at check in the patients received a blue card labeled with their information and space for the various medical professionals to write on. At triage all of my new friends handed over the cards to have blood pressure, temperature, and chief complaint recorded. My cousin Lindsey was triaging with a translator relaying information to her. Each child received a sticker on their foreheads before leaving, bringing many smiles.

We then proceeded to the small, original church building of Bombo Pentecostal Church, salmon colored with cement floors, around an eighth of the size of the worship center being built. The church has grown in numbers greatly. BPC focuses on discipleship, connecting people to others, providing care, and encouraging continual pursuit of Christ. People walked into the small building with blue cards in hand and sat in rows of school desks pushed together. A church volunteer spoke of Jesus as the colorfully dressed people of Bombo waited to move to their first stop of the clinic. The volunteers spoke with passion of Jesus, the Luganda language flowing quickly from their lips as adults nodded and murmured agreement. They sat in this small building with lots of windows for only a few minutes. But those few minutes were used to speak of the Man who brought not just health of flesh while He was on earth, but health of spirit. The rows kept shifting and our turn came to go to Pediatrics.

They were ushered into in an exam room and I followed. All the children took turns being checked by one of the doctors from America, Dr. Bisi, or one of the Ugandan pediatricians, Dr. Morris. They stood against the dusty, crumbly pink walls, patiently waiting their turn. Dr. Bisi gave out Tootsie Rolls to the children who came through her care. I watched one of the younger girls turn it around and around in her hands, holding it like a treasure, carefully pinching the white ends and slowly pulling it open. She popped the chewy chocolate straight in her mouth and smiled with wide eyed wonder. The children received multivitamins from the pediatricians and a prescription for deworming.

We proceeded back down stairs and back into the sun having increased in warmth since we entered pediatrics. At the bottom of the stairs, Jeniffer pointing first to her eyes then gesturing toward the whole of the clinic, asked me where “eyes” were. I nodded in understanding, the moment I took a step tiny hands wove into mine. She followed the train of little brown bodies following me to ophthalmology. Jeniffer took a seat in line along the outer orange wall of a one story building to await an eye exam. This first exam was stationed outside as it required more room than the small blue tarp exam rooms could provide, the visual acuity test using a chart of letters to identify clarity of vision.

I sat with the kids in the dirt, observing the proceedings. The woman running the test outside was confused as to why we were sitting in the dirt in the sun, content to simply watch. Gitta was in my lap, holding my hands, the others leaning against me examining their blue cards and boxes of multivitamin again and again. We looked at pictures on my camera and watched Jeniffer move seats, closer and closer to the front of the exam line. Eventually we were ushered away, out of the blazing sun into the shade. I ran around for a few minutes doing menial errands and every time I would walk past the white tent the kids resided under, even from a distance, Gitta would see me and stand up making eye contact and waving. He was always finding me as I hung in the background during our day at the clinic, trying to stay out of the way. His head would swivel in all directions until he found my bright muzungu skin. Sometimes all it takes is an open hand and a camera to make new friends.

Jeniffer was finally called into ophthalmology and I followed. I think ophthalmology is one of the most beautiful things. The careful and detailed work of looking into the eyes, the receivers of light and color, organisms so affected by even the smallest deviation from 20/20, and all the gadgets and gizmos for analyzing, identifying the small change needed to correct is a detailed process. The ability to see is such a forgotten blessing until things start to deteriorate. Jeniffer needed glasses. A prescription was identified and we went to the last station of ophthalmology, the testing of prescription to make sure the inability to read would be alleviated. I held my camera to my own eye, watching through glass and mirrors as the small, phoropter like glasses were placed on Jeniffer and lenses switched until the small print of Bible she held in front of her face became clear. A peaceful smile crept onto her face and a number was written on her blue card then recorded in a large log book before we went out again into the sun to our final destination: the pharmacy.

The people of Uganda are good at waiting I thought as my six friends took their seats in the final place of waiting outside the pharmacy. There are no smart phones, books or magazine to distract. People of all ages sat in the stiff white chairs and talked with one another, or simply rested, peacefully. I image the same scene in America, but people angry their prescriptions were taking long, searching for outlets to charge phones, arms crossed and far apart from one another. In Uganda, there were no rows of chairs, but clumps facing one another, old leaning against the young forming an amoeba shaded in blues, yellows, reds, and purples. Jeniffer and the kids were called to get their baggies of prescriptions and the glasses and our two hours together came to an end.

I had Jeniffer put on her glasses so I could take a picture before she left, the conclusion to my story. I turned my camera to show her the portrait. She smiled so big and reached out to hug me, saying thank you in my ear. Her health concerns were not fatal, her needs the average of what we saw at the clinic, the children health and energetic despite sun and a long morning. But the glasses changed her outlook, brought her joy, and the kids left skipping and smiling with the knowledge they received health care from the muzungus. Refrains of, “Bye, muzungu!” were called from small sweet voices. Gitta was walking backwards, waving goodbye back up the crumbly red dirt driveway. I watched them go left on the road they had lined many hours before. The warm sun beat down on the top of my head as I finally turned my back on the entrance and walked the opposite direction of Jeniffer and the children, of Gitta and his companions. They walked away with a bag containing simple health care items, but they walked a little taller, their smiles a little bigger, their eyes seeming bright with what was once again ignited in the two hours at the clinic: hope.